How targeted data insights can help close America’s hunger gap

Food Insecurity is a Pressing National Issue, Made Worse by the Covid-19 Pandemic

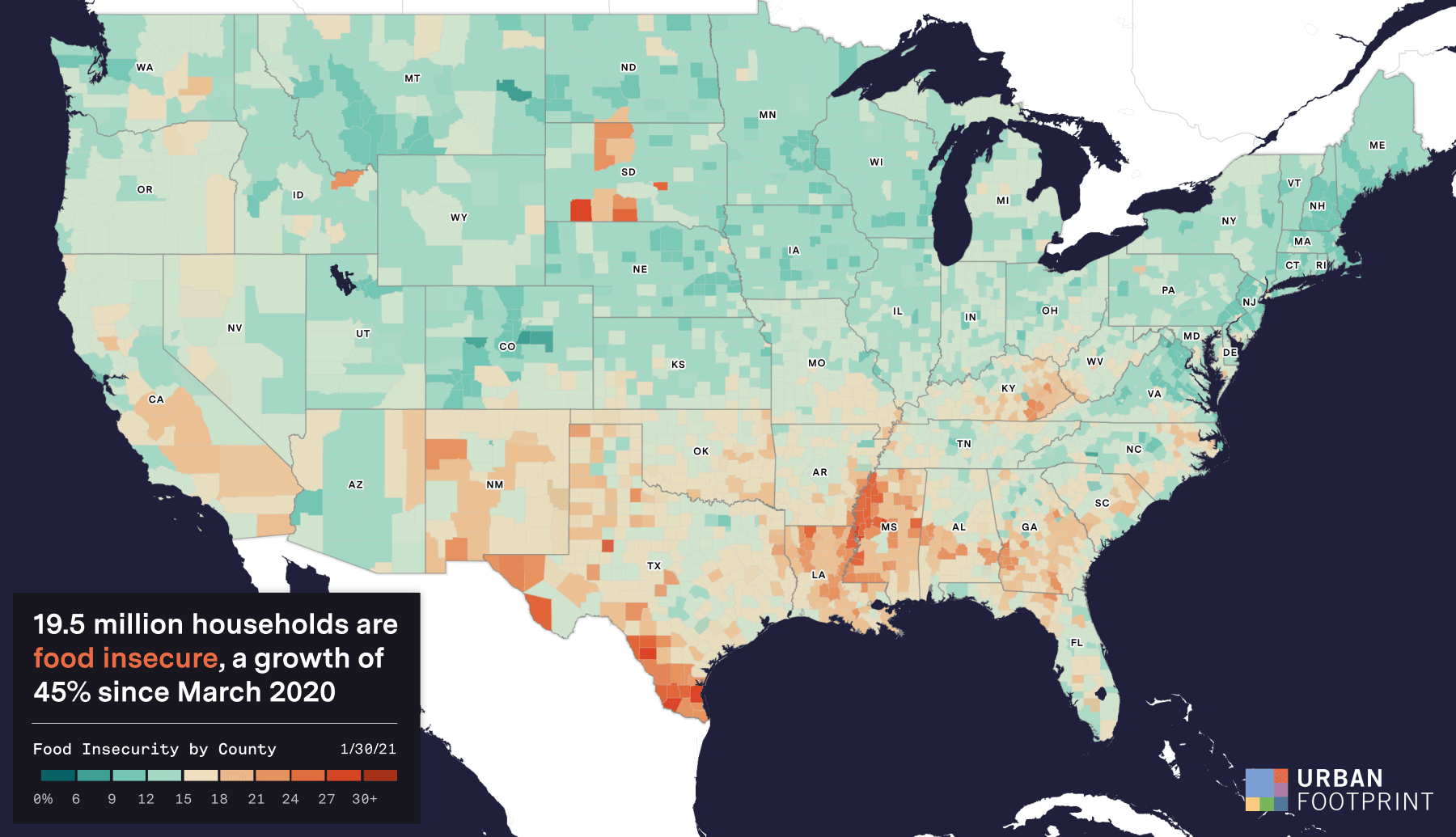

Hunger is an acute challenge for far too many American households. This was true before the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is even more pressing today. Across the US, 19.5 million households are food insecure—defined as those without the financial resources needed for consistent access to enough food—a growth of 45% since March 2020. More acutely, nearly 12.2 million of these households report food insufficiency, or not having enough food to eat at some point in the last week. This striking number suggests that existing relief programs and aid are not meeting their needs.

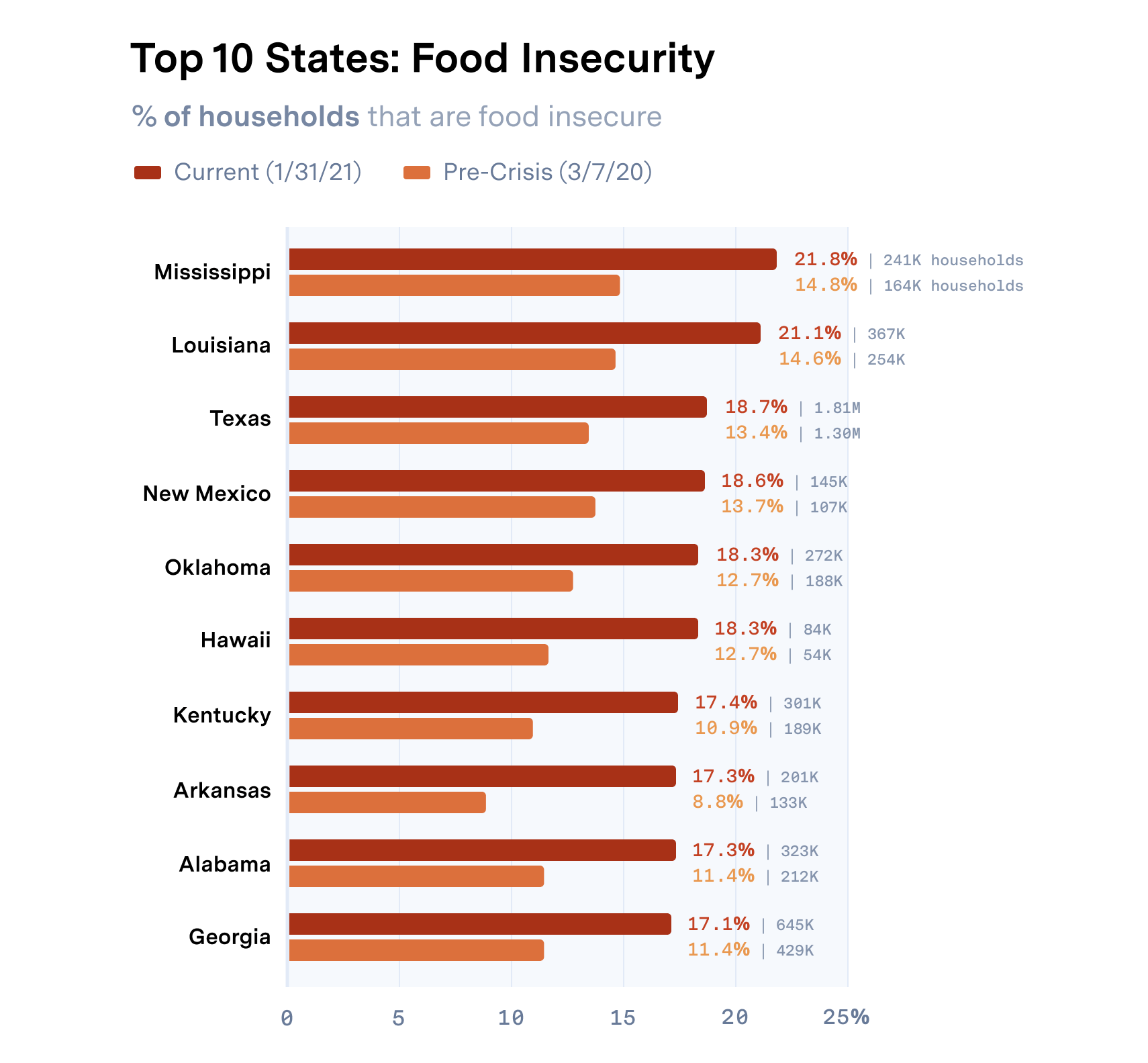

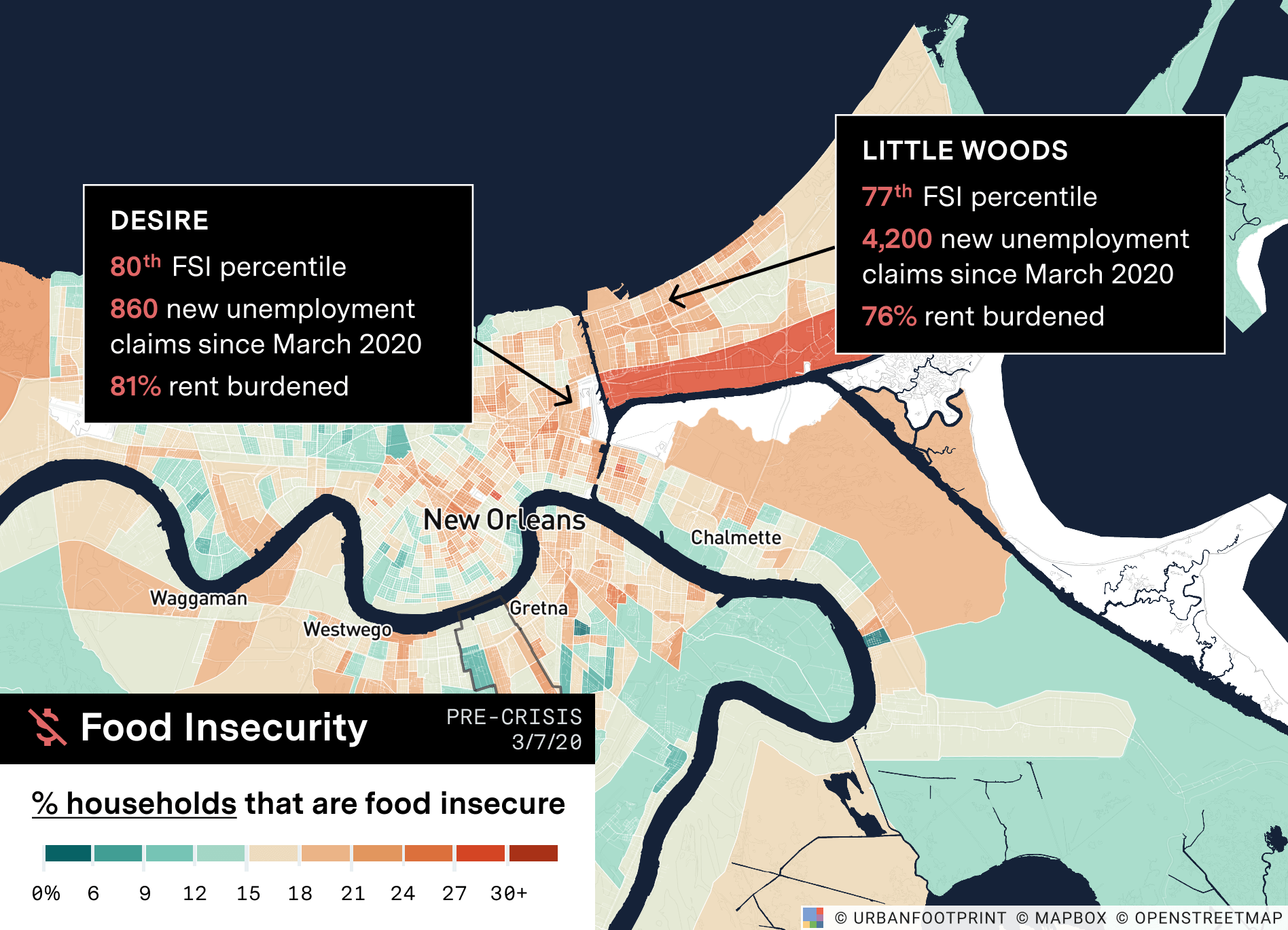

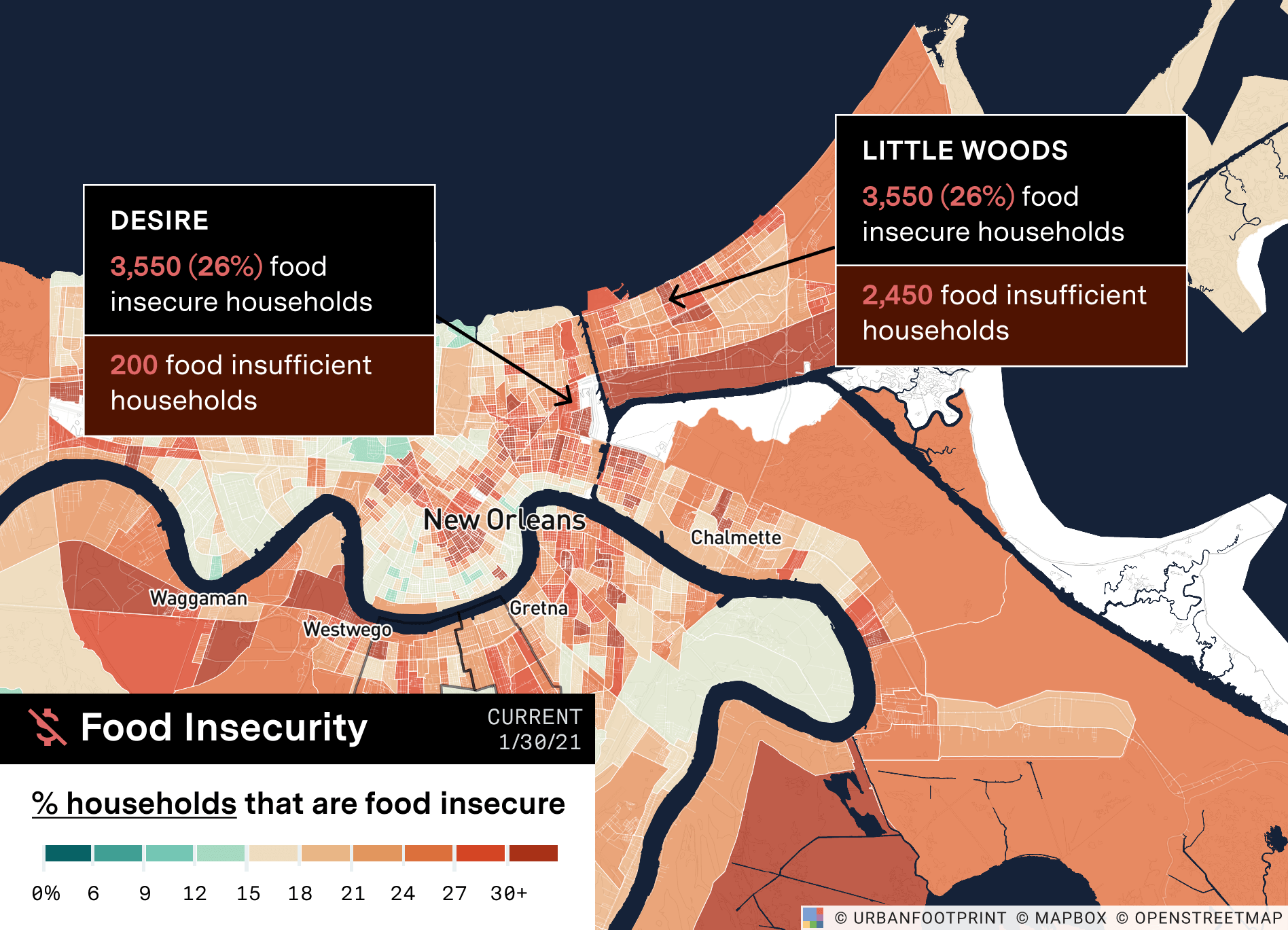

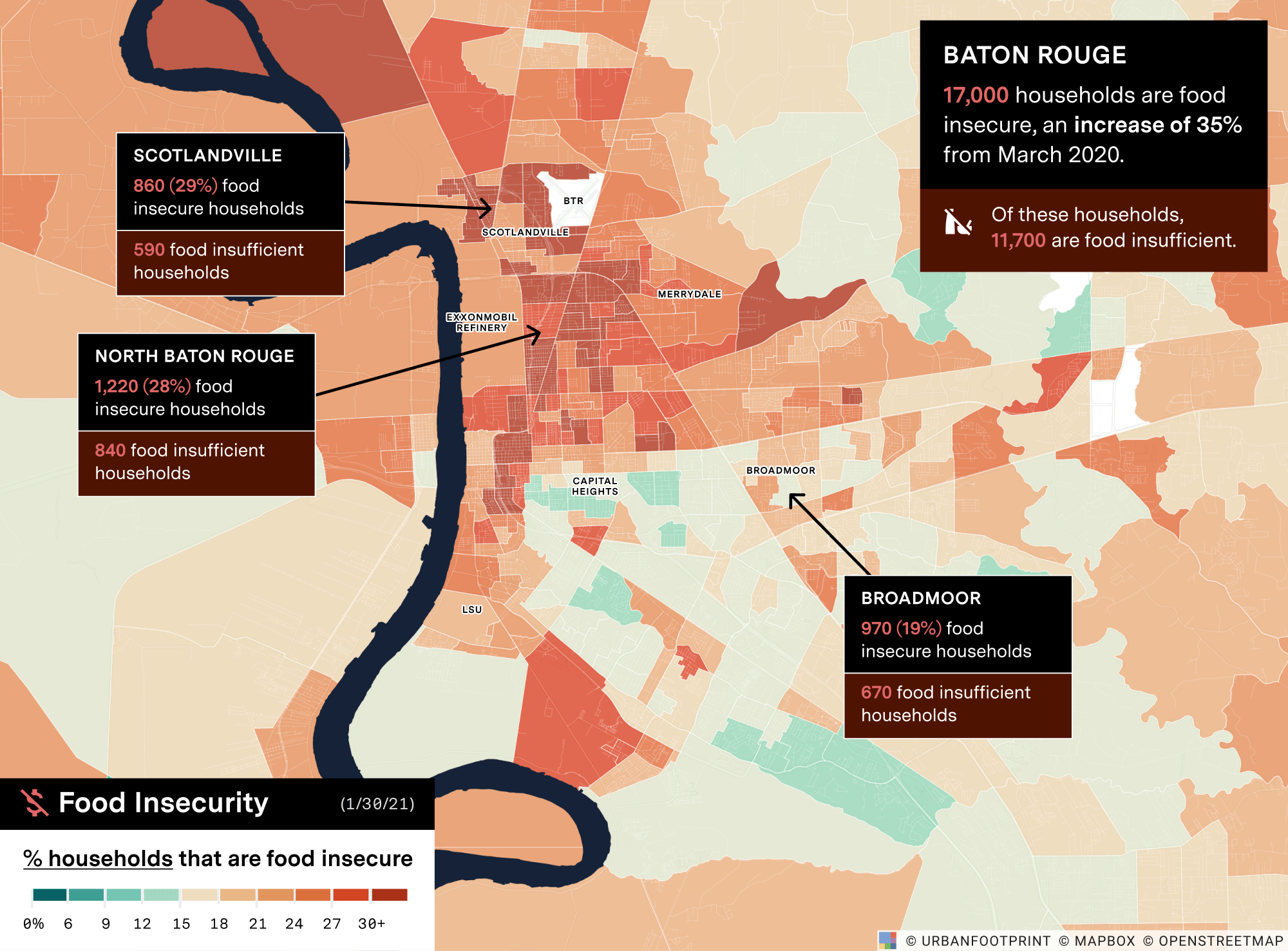

Further complicating the crisis is its uneven distribution. Nine of the ten states with the highest rates of food insecurity are concentrated in the south. In some of those hardest hit, like Louisiana, more than 21% of the population is food insecure, a growth of 113,000 since the beginning of the pandemic. Even more pronounced are the rates of food insufficiency in these states, with more than 253,000 people in Louisiana (15% of the population) reporting not getting enough food to eat at some point in the last week.

Within these hardest-hit states, communities of color are at significantly higher risk. In Louisiana, 23% of Black households are food insufficient compared with 7% of white households.

In Louisiana’s Orleans Parish, more than 33,000 households are food insecure today, a 29% increase since the start of the COVID-19 crisis. In some lower income and non-white neighborhoods in New Orleans, food insecurity can impact as many as 35% of households.

The American Rescue Plan’s Attack on Hunger

The $1.9T American Rescue Plan, recently signed into law by President Biden, is one of the most ambitious plans to reduce poverty in American history. The Plan has a strong focus on solving the hunger crisis in America, and puts special emphasis on targeting assistance to the lowest income and hardest-to-reach households.

For example, the Plan extends emergency funding to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides low income Americans with access to healthy groceries, but notes that over 20 million of the lowest income households have received very little or no benefits since the start of the pandemic.

The Plan also extends funding for Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which provides tailored nutrition assistance to new moms, infants and children in the first five years of life. Only half of eligible low income individuals were enrolled in 2017, despite a dramatic increase in the number of children living in households facing food hardship.

Technology to Reach the Most Vulnerable in Louisiana

Federal programs like SNAP and WIC, and the broader ecosystem of community groups and food bank networks providing emergency relief, face three critical and compounding challenges:

- Identifying the extent of need: Expanding food relief funds and resources to meet growing demand.

- Mapping and allocating the need: Targeting food relief logistics and resource distribution to those in need based on up-to-date information.

- Closing gaps between need and relief distribution: Reaching and serving those in need who are unaware of programs or cannot access them via standard channels.

At the start of the pandemic, UrbanFootprint joined forces with the Center for Planning Excellence (CPEX), a planning and policy non-profit organization, because, in the words of CPEX President & CEO Camille Manning-Broome, “the COVID-19 pandemic quickly revealed itself as an interwoven health, economic, and social crisis threatening community stability. We recognized that the distribution of these impacts were uneven and place-based, and saw the opportunity to harness the power of planning and mapping to target relief to the people most in need.”

As we began our work, it became clear that traditional methods were not going to be able to effectively map and measure the rapid growth in food insecurity. Modern data and software were poised to close this information gap and moreover could be deployed to hyper-target aid and outreach to the hardest to reach populations.

As noted by Shavana Howard, who runs the SNAP Program for the State of Louisiana: “Having data that can help us better target resources to Louisiana’s most food insecure households would be a game changer. It would allow us to reach out directly to these individuals and families.”

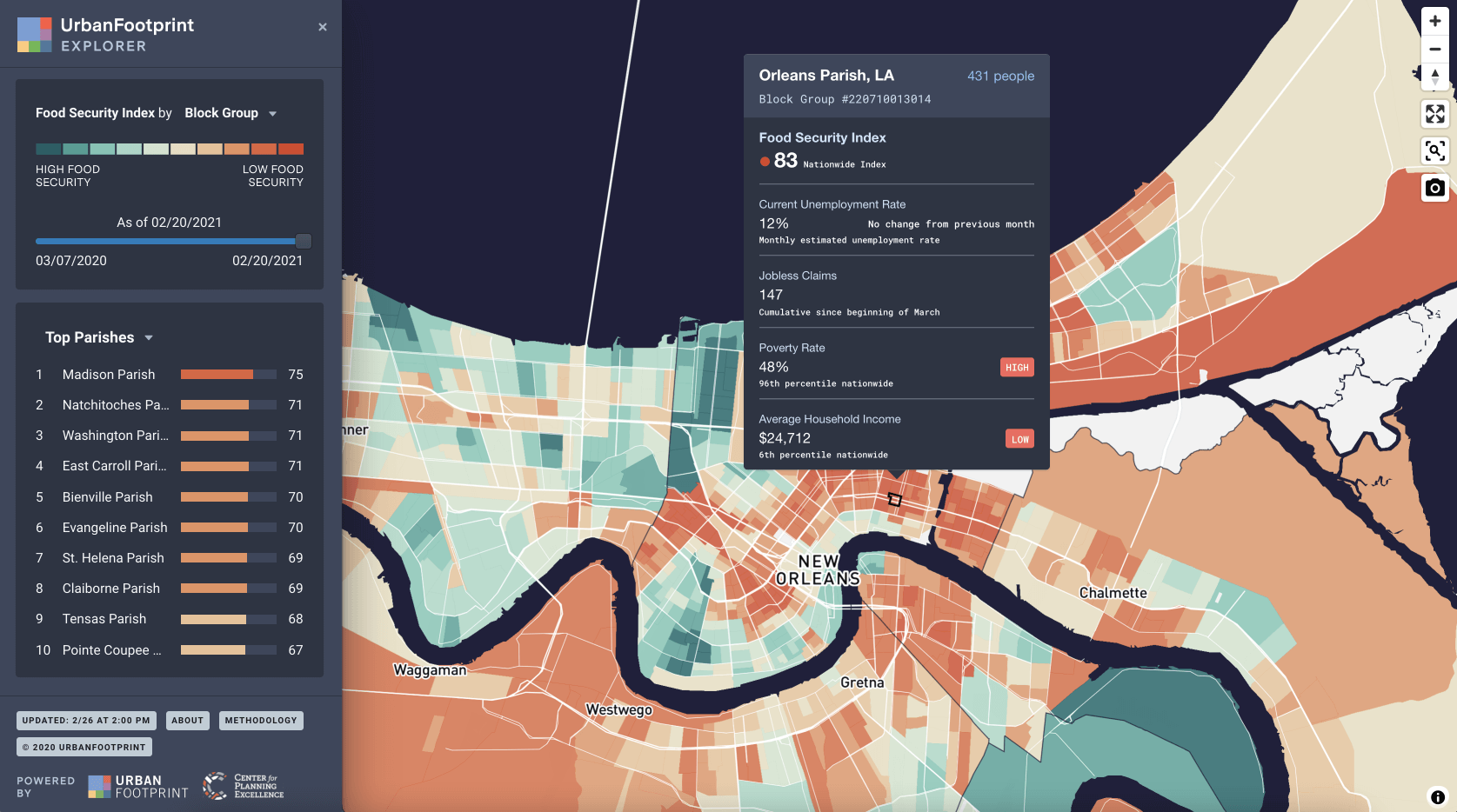

With our partners in Louisiana, we set out to target those resources with timely, actionable information. The result is UrbanFootprint Food Security Insights (FSI), the first-ever dynamic data to track the scale and distribution of the evolving food security crisis across communities. FSI data is updated every two weeks with estimates down to the neighborhood level, allowing state agencies and front-line food bank networks to identify communities with the greatest need but the lowest levels of enrollment in programs like SNAP, and reach out to these households through highly targeted online or in-person campaigns.

Food Security Insights In Action

While the FSI has existed for less than a year, we’ve had the privilege of working with some of the most important players working to end hunger in Louisiana. These partners have given us profound insight into what it’s like to be on the front lines of this crisis, which in turn allows us to continue to improve FSI in ways that help these organizations achieve their goals.

For example, Feeding Louisiana, a state-wide food security policy, advocacy, and fundraising organization, is using FSI to advocate for strong federal and state hunger relief programs, and to coordinate action amongst their member food banks. Korey Patty, CEO of Feeding Louisiana, said that “we’ve always known how many meals our food bank network partners provide and how many people are enrolled in programs like SNAP. What we’ve been missing is the denominator—a clear understanding of how many households are food insecure—and where these households are located. FSI fills this gap, allowing us to understand the true scope and scale of the problem, and the progress we’re making.”

Another partner, Second Harvest, a leading food bank network, is building a partnership network to support their emergency food distribution work in ten rural parishes. By overlaying the service areas of potential partners against the overall food insecurity in a community, Second Harvest can identify organizations that are geographically well suited to reach the most underserved communities. In the same vein, The Louisiana Budget Project, a policy advocacy organization, is using FSI to help New Orleans Public Schools identify schools in high-need communities to enroll in their No Kid Hungry Meal Program.

Finally, the Louisiana Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), the organization responsible for SNAP and other benefit programs in Louisiana, is slated to use the FSI to support front-line teams and local partners to help close the ‘SNAP Gap’—targeting their outreach to hard-to-reach communities that have low program participation rates. DCFS will also use FSI to communicate internally to its 1,850-member staff, and measure their progress towards achieving their strategic goals.

Expanding FSI in 2021 to Help Millions of Households

Last year, we began putting our platform to use to help eliminate hunger because we wanted to do our part in a time of crisis. What we realized along the way is that we have an opportunity to help build a new social contract on the values of equity and resilience.

We’re doubling down on this vision for the future by continuing to invest in the data and technology behind FSI and the broader UrbanFootprint platform. We’ll also continue to work with our partners to make these tools accessible to government agencies, advocacy organizations, and food bank networks, in Louisiana and across the country, to help create a new standard for equitable resource distribution.

Contributors

- Written in collaboration with Joshua Goldstein

- Maps and graphics by Stephen Kennedy